MAISON INTÈGRE GALLERY IN LISBON

MAISON INTÈGRE GALLERY IN LISBON

During Lisbon Design Week, we unveiled our first location. A space a the intersection of a studio and a gallery, where our bronze pieces and a collection of antiques objects are showcased.

Located at Travesso do Rosário, 20 in Lisbon, the gallery is now open on Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays from 10.30am to 6.30pm. We can also organise private visits by appointment.

THE COLLECTION BY MARION MAILAENDER

NEW COLLECTION

Designed by Marion Mailaender

In 2021, Marion Mailaender visited us in Ouagadougou to discover the craftsmanship of burkinabè bronze and to work together on a new collection of pieces.

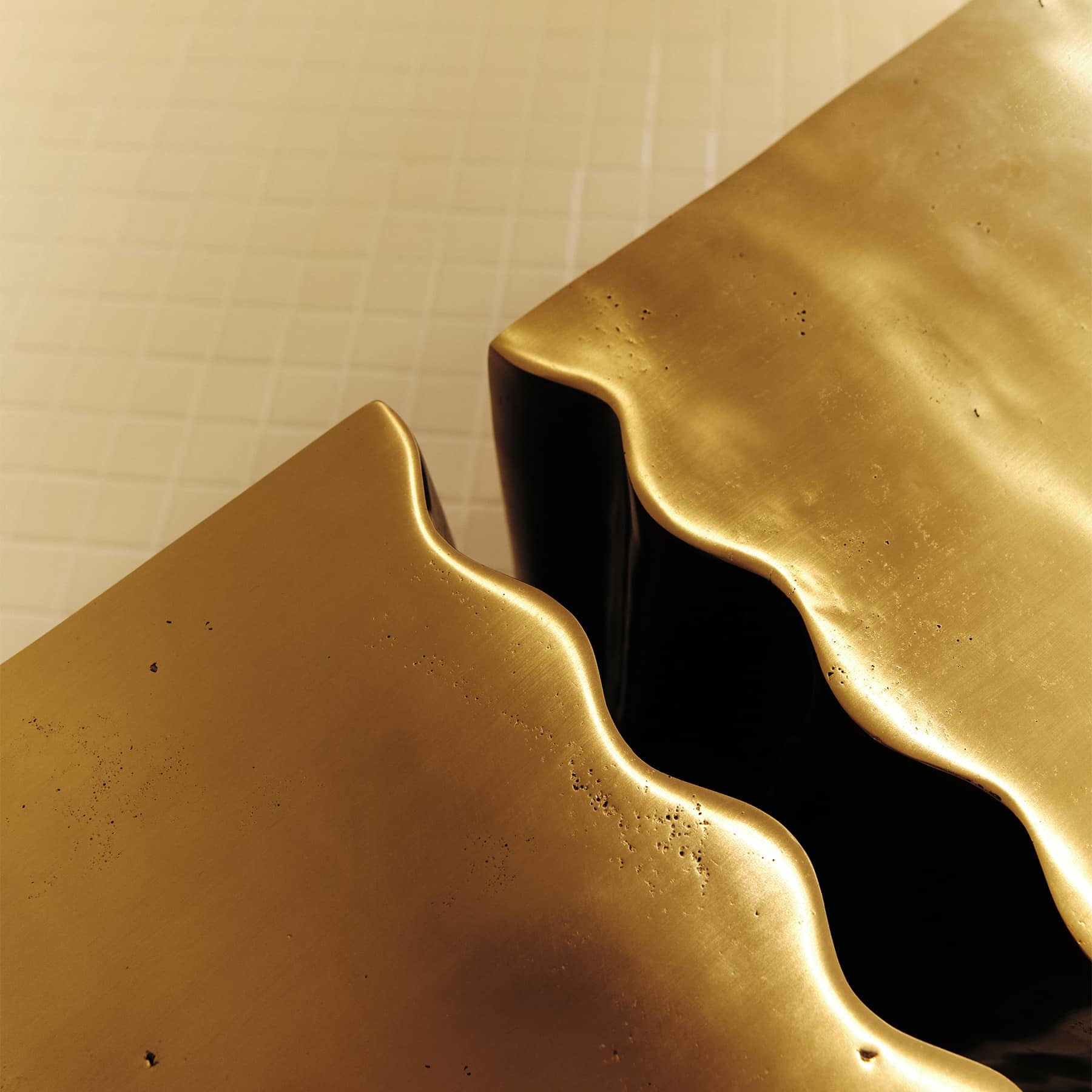

The first ideas emerged around corrugated iron. This popular, very functional, and durable material is ubiquitous in the city. It is used both on roofs and as a decorative element for the interior and exterior walls of homes.Corrugated iron painted in pink can be found as the storefront of a hairdresser, or in the colors of Burkina Faso in front of a PMU’B (Burkina Faso horse racing betting shop).

It is from this formal principle that the collaboration with Marion began, leading to the creation of four interlocking pieces that always follow the same rhythm of this iconic corrugated iron. They are being presented for the first time on the occasion of the Design Parade in Toulon, where Marion Mailaender, president of the jury for the 2024 edition, proposed “Résidence Vue Mer,” a brilliant exhibition, true to her image.

À PROPOS DE LA DESIGNER

Marion Mailaender

Marion Mailaender is a Marseilles-based designer who likes to seize on cultural codes, customs and popular forms. She brings them together to create poetic, evocative and highly narrative objects. She uses everyday details that may seem insignificant, but which nonetheless form the basis of a memory to be reactivated. Marion questions our relationship with space and takes a tender look at what she calls architectural moments.

PIECES

Available on order

INTERIOR PIECES

INTERIOR PIECES

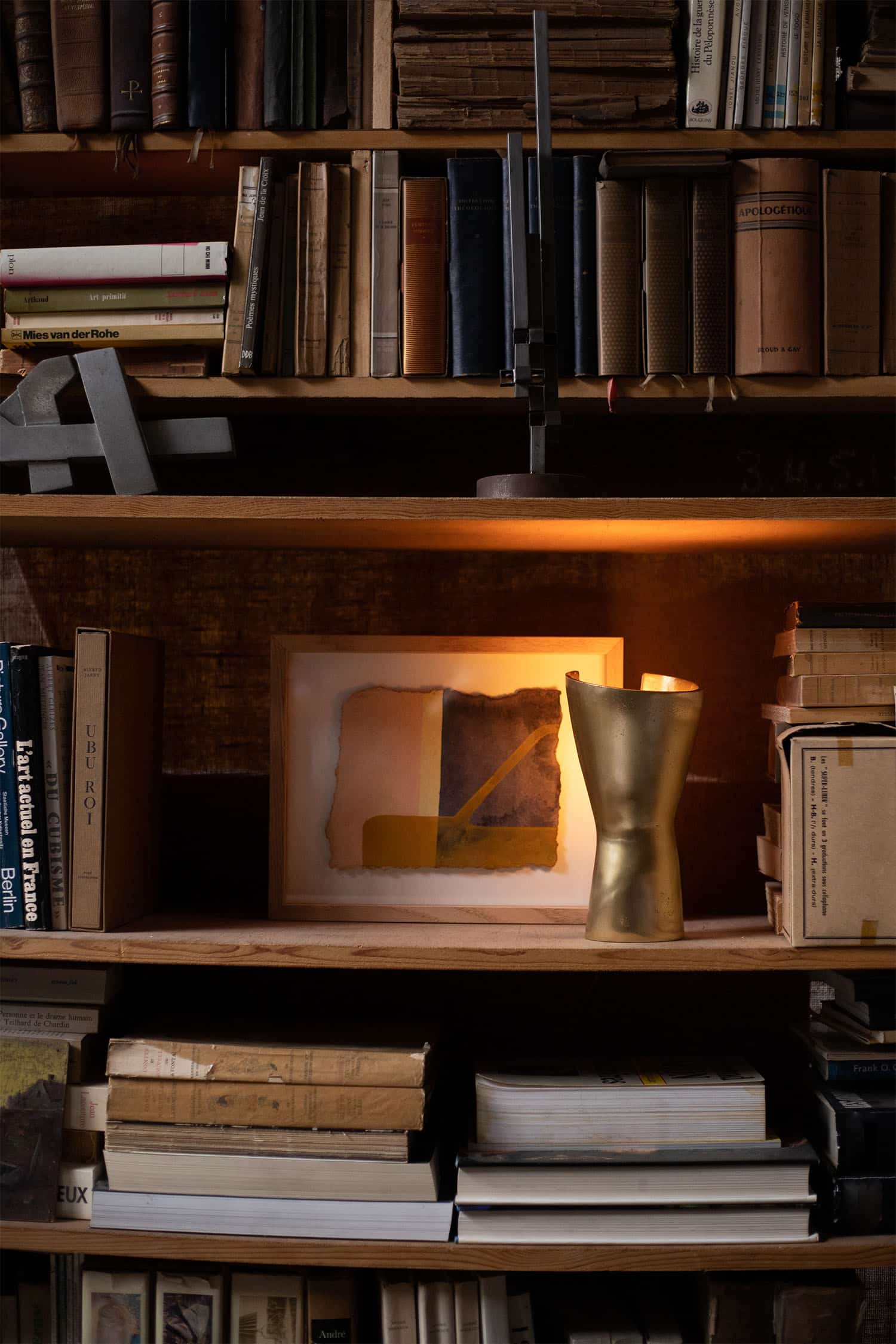

Fragments of interior stories where Maison Intègre has settled for a while...

EXHIBITION BY ANNE SIROT AT ATELIER LARDEUR

Anne Sirot invited Maison Intègre to organize a duo exhibition with artist Chloé Leveque.

Chloé Levesque’s ink and pencil drawings and Maison Intègre’s bronze pieces come together in the Atelier Lardeur, a former stained glass workshop nestled in a courtyard in Paris’s 6th arrondissement, a place charged with history and light.

From May 26 to June 2, 2024

©Marion Saupin

UNIQUE INTERIORS BY RODOLPHE PARENTE

Ingenuity, sensitivity to craftsmanship, expressive materials, a certain fantasia and openness to contemporary uses are distilled and sublimated in the projects of designer-architect Rodolphe Parente. They all reveal a desire for the imaginary, for contrast and precision, for a constantly reinvented modernity. His creations embody a luxury tinted with lightness, encourage curiosity and honor art.

©Claire Israel

THE VISION OF HELENE VAN MARCKE BY THOMAS DE BRUYNE (CAFEINE)

Interior designer Hélène Van Marcke has transformed a Parisian “chambre de bonne” into a penthouse on Avenue Marceau. The architecture remains sober and timeless, allowing the stunning art and design collection to add color to the rooms. A mesmerizing mix of African elements by Maison Intègre and more avant-garde pieces by Van Severen, Paulin et Charpin, Gino Sarfatti...

©Thomas De Bruyne (Cafeine)

RAPHAËL ET NOËLIE SAWADOGO

RAPHAËL AND NOËLIE SAWADOGO

Designers and weavers

“I learned to dye and I liked it, I love creating!”

Raphaël Sawadogo has already lived more than ten lives. In wood craftship, in certification, abroad, he worked in many different jobs, sometimes very well paid, until becoming an employee of a weaving workshop. “I was the boss’s right-hand man, a long-time friend, I helped him in particular with administrative management.” Then his friend tells him of an imminent departure to the United States and the closure of the workshop. “I was in danger!”. It was four years ago. He decides to learn dyeing, and it’s a revelation. “I really like it, and it provides a living for my family.”

At his side, Noëlie, his wife, creates and weaves the prototypes. The couple is settled in the courtyard of their house in Cissin, Ouagadougou. A 10-meter loom is there, carrying the threads of the creation in progress.

“We weave Faso dan Fani, from local cotton, organic one as often as possible.”

Faso dan Fani, which has returned to fashion thanks to the national preference given to local creations, has not generated any increase in activity among them. “But we have added value: we weave 40 thread, while the others weave 20.” A much finer and more elegant thread than the traditional dan Fani, which may be a little heavy to carry sometimes.

Raphaël and Noëlie also rely on sobriety to differentiate themselves: “no golden threads here, nor garish patterns”. In fact, their loincloths are either “dirty white”, that is to say ecru, or pastel colors. Because Raphaël favors the natural dyeing of his yarn, based on leaves, roots, bark or stones. And even when he has to use chemical dyes for financial reasons, he sticks to a range of colors close to those obtained by natural dyes. Once the yarn has been cleaned by boiling, the pattern created by Noëlie and the prototype woven, four women will weave the loincloths which will be sent to customers.

Raphaël works with individuals but also couturiers, and not the least. François 1er, a renowned Burkinabè designer, was seduced by the finesse of his Dan Fani and the delicacy of his patterns. “And we are among the only ones to weave 45 cm wide, where the others tend to weave 30 cm wide.” The Sawadogo couple’s demands for final quality and the difficulty of weaving such a fine thread mean that some women refuse to weave, because “you have to be calm, listen to advice and accept criticism” emphasizes Raphaël.

In March 2016, the revival of Dan Fani and the presidential decision to produce a national loincloth in this cotton caused a thread break. “There were none left, anywhere”, remembers Raphaël, who had to part with 6 of his weavers. Today, they have settled back into other activities and do not wish to return. Raphaël is therefore faced with the problem of every growing craftsman. Not enough hands to increase the quantity, and therefore not enough income to hire 6 new employees and invest in the equipment that goes with them. But the tenacity and professionalism of the couple suggests that this state will not last forever, thanks to their numerous recommendations.

Moreover, the objectives are clear: “I have acquired a small piece of land, I want to build a workshop there to bring together all the stages from dyeing to the exhibition and sale of finished products.” And thus make the courtyard of their little house playable for their three children and the dog Tex.

“Faso Dan Fani weaving requires seriousness and precision to obtain a quality product that will stand out.”

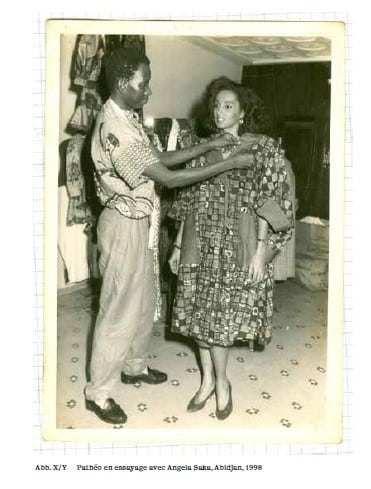

FASO DAN FANI

FASO DAN FANI

Woven loincloth of the homeland

If ever there was a symbol of Burkinabe patriotism, it’s Faso dan Fani. In a country where the cultivation of non-genetically modified cotton is one of the country’s main sources of income, and where the tradition of weaving goes back a long way, these heavy cotton loincloths quickly became indispensable both for clothing and for furnishing and decorative fabrics.

“In all the villages of Burkina Faso, we know how to grow cotton. In all the villages, women know how to spin cotton, men know how to weave this thread into loincloths and other men know how to sew these loincloths into clothes. We must not be a slave to what others produce.”Thomas Sankara

When Captain Thomas Sankara came to power in the mid-1980s, Faso Dan Fani became a national symbol and a promoter of local know-how. Determined to promote the emancipation of women through work and the development of national production, Thomas Sankara issued a decree requiring his civil servants to wear Faso Dan Fani. “Wearing Faso Dan Fani is an economic, cultural and political act of defiance against imperialism”, said Thomas Sankara, whose political inspiration was essentially based on communism and anti-colonialism.

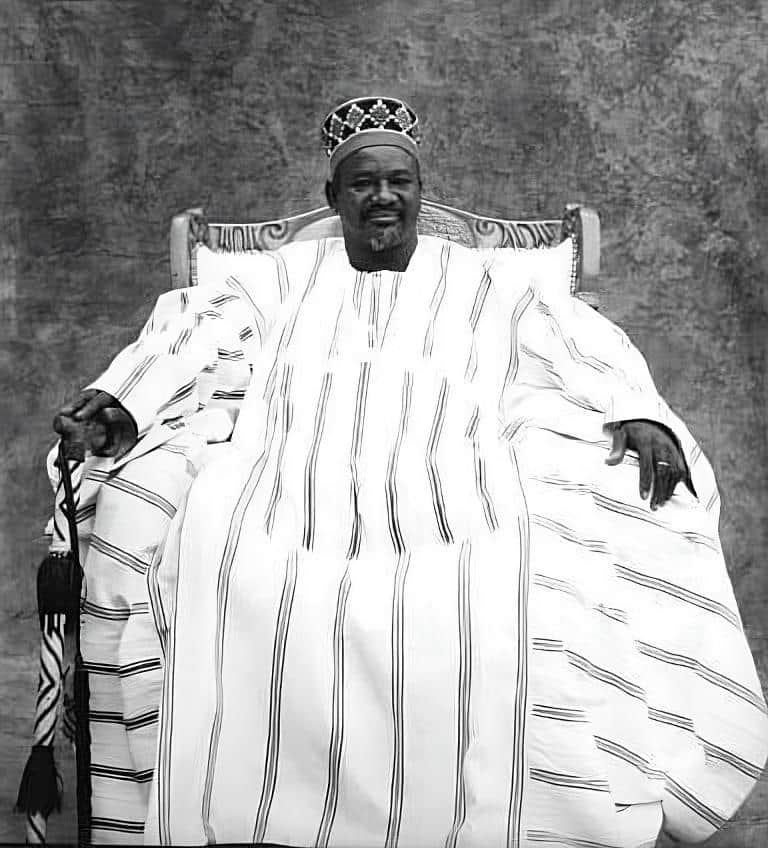

Although the daily use of this loincloth fell into disuse after Sankara’s death and the implementation of a much more liberal policy, the Faso Dan Fani has always remained the basis for the production of festive and ceremonial clothing, with the Naba – village chiefs – wearing it for every occasion. The first of these, the Mogho Naba, emperor of the Mossi, always wore a Faso Dan Fani when appearing in public or receiving audiences in his palace in Ouagadougou.

The revolution that took place in 2014, which ousted the dictator in place since the death of Sankara, raised an incredible wind of patriotism among Burkinabè. Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, President democratically elected at the end of 2015, brought the port of Faso Dan Fani up to date, himself wearing it at each of his appearances, including on official trips abroad. If the use of Dan Fani has not been made compulsory this time, it is however very favored. Each political demonstration sees the statesmen dressed in the traditional outfit woven in this heavy cotton, and the so-called “March 8” loincloth, published each year in honor of World Women’s Day for Equal Rights, and traditionally offered by all employers to their employees, is now from Faso Dan Fani.

Robust and natural, the Faso Dan Fani has become the symbol of a Nation proud of its roots and its know-how.

“Today Faso Dan Fani is highly valued around the world. It is the most expensive and best African fabric nowadays."Pathé Ouedraogo, known as Pathé'O, Ivorian designer

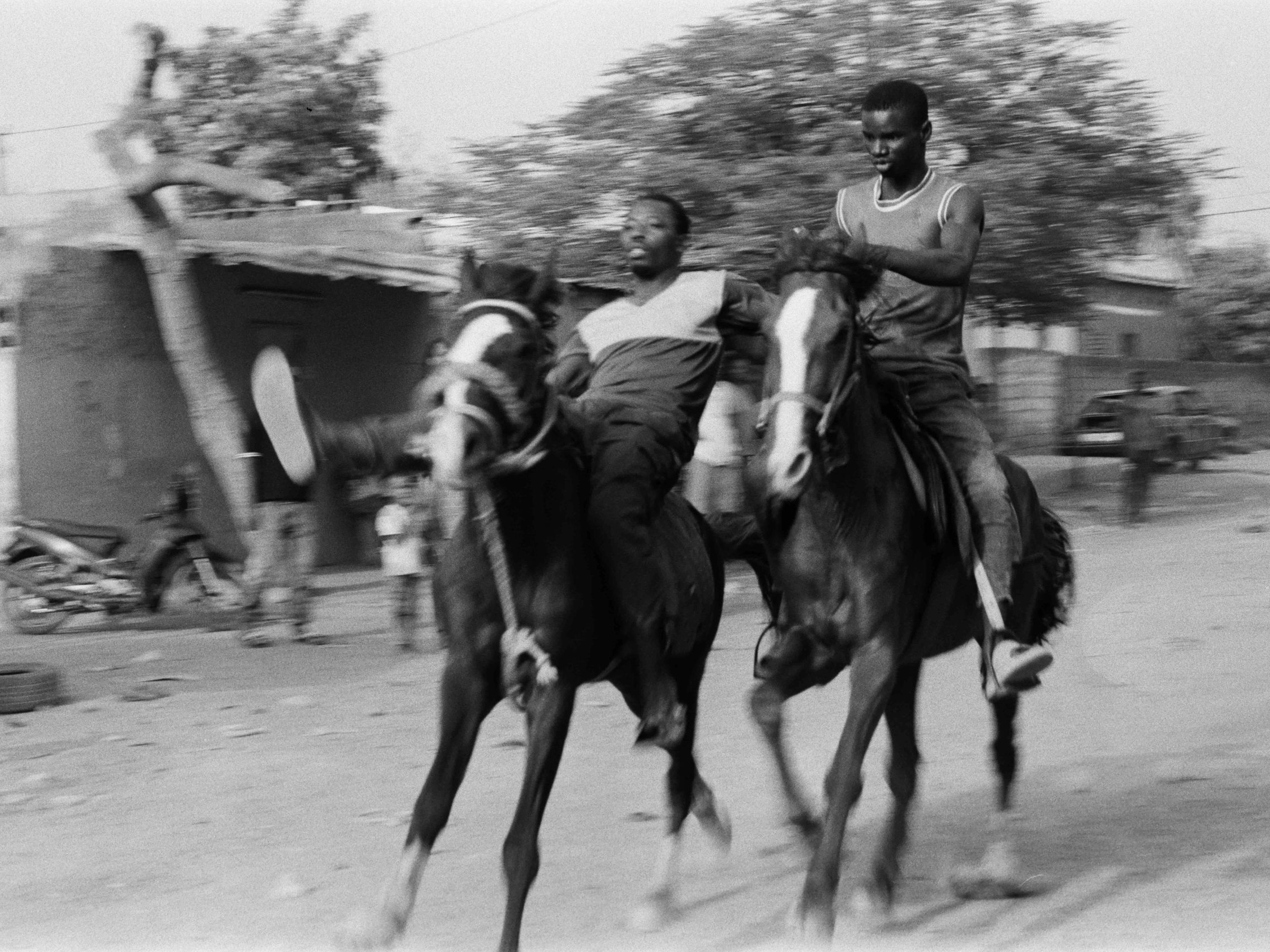

HORSEMEN FROM BURKINA FASO

HORSEMEN FROM BURKINA FASO

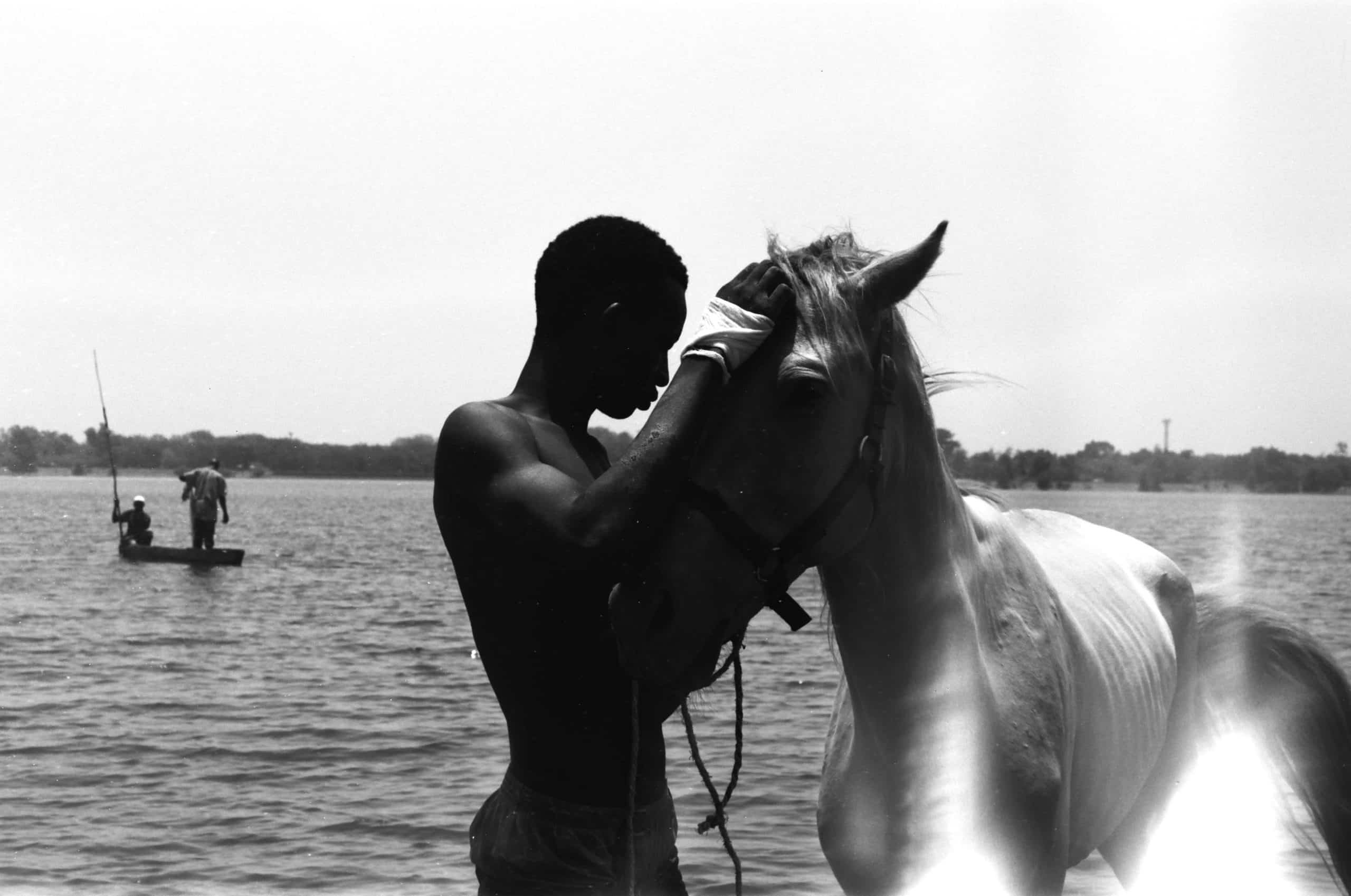

If you come to Burkina Faso, it’s not uncommon to come across a horse rider pacing the streets. The horse, emblem of the country, has a very close relationship with the burkinabè people.

This connection originated in the legendary tale of Princess Yennenga and an exiled Malinke prince. Yennenga means “slender”, and is the founder of the Moogo kingdom uniting the Mossi peoples of present-day Burkina Faso. She was the daughter of King Nedega, an authoritarian and loyal king who ruled over the Dagomb peoples. The princess was passionate about horses, but despaired of being able to ride as men did.

Rebellious and reckless, she convinced her father to allow her to ride alongside him and became a fierce warrior. Following a dispute with her father, he threw her into prison, but the princess managed to escape and rode away on her favorite mount, a white stallion. During her escape, she met Prince Malinké, with whom she fell madly in love. The result was Prince Ouedraogo, meaning “stallion” or “male horse”.

Today, the “Ouedraogo” surname is one of the most common in Burkina Faso. The white horse on which the princess escaped has become the country’s national emblem.

This legend, passed down exclusively through Mossi oral tradition, has maintained a widespread passion for horses and their sacred role in the country. There was also a prestigious cavalry in medieval times, which disappeared with colonialism. Since then, this tradition has left a strong cultural legacy and a real passion for horses throughout the country.

The equestrian tradition has resurfaced in a more marginal, urban form. It is developing alongside Burkina Faso’s ancient equestrian tradition, bringing it a new lease of life and a youth proud of its origins.

Only a few of the country’s wealthiest families own horses in the city, so young riders take to the streets and mingle with the capital’s frenetic traffic. Meeting in front of a bar or nightclub, they can be found at ceremonies or shows. The equestrian cult of nobility and beauty is remembered by all. It’s also common to come across horses roaming freely, sometimes stopping in front of houses simply to graze – they are the kings of the city.

The collection by Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance

NEW COLLECTION

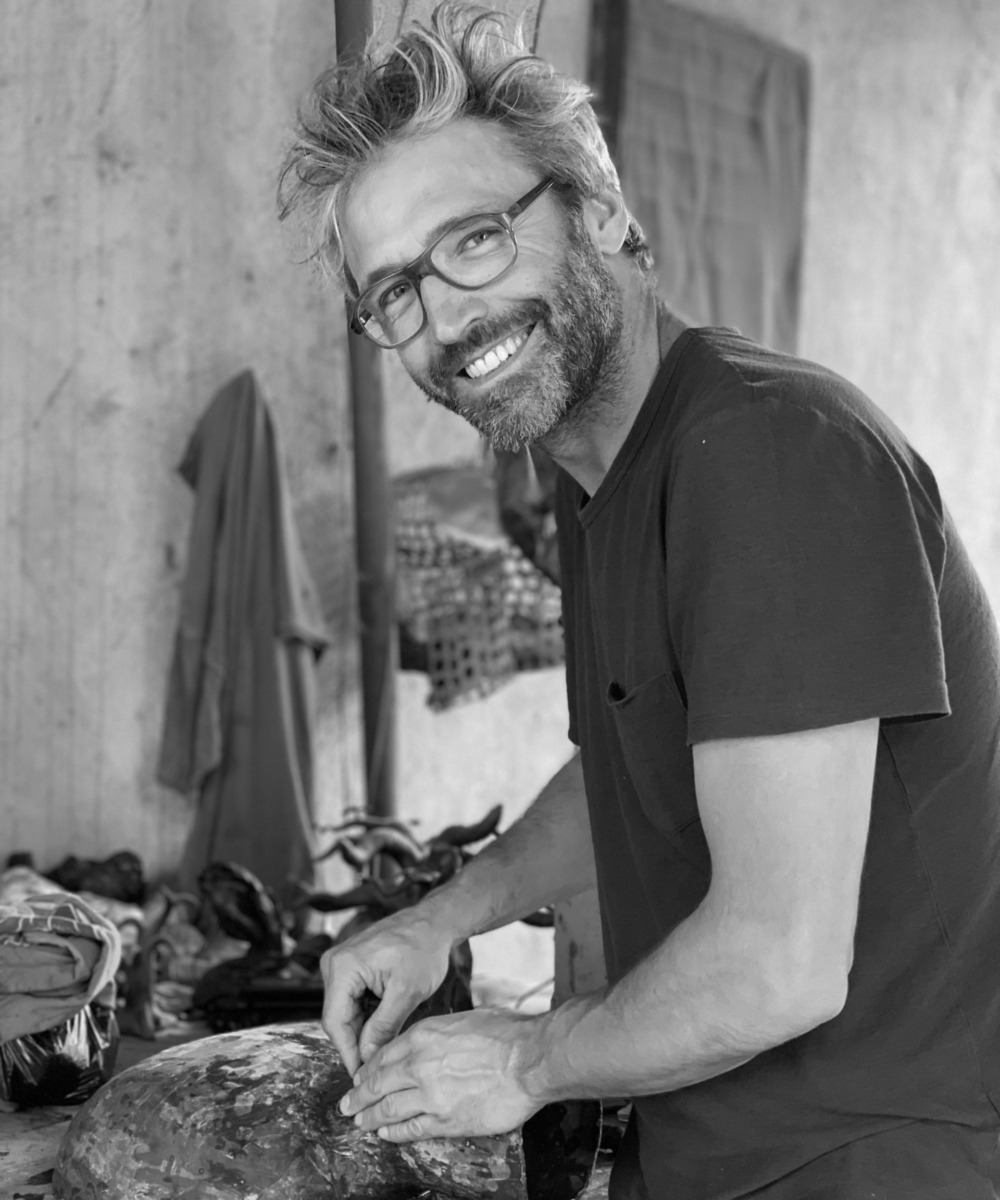

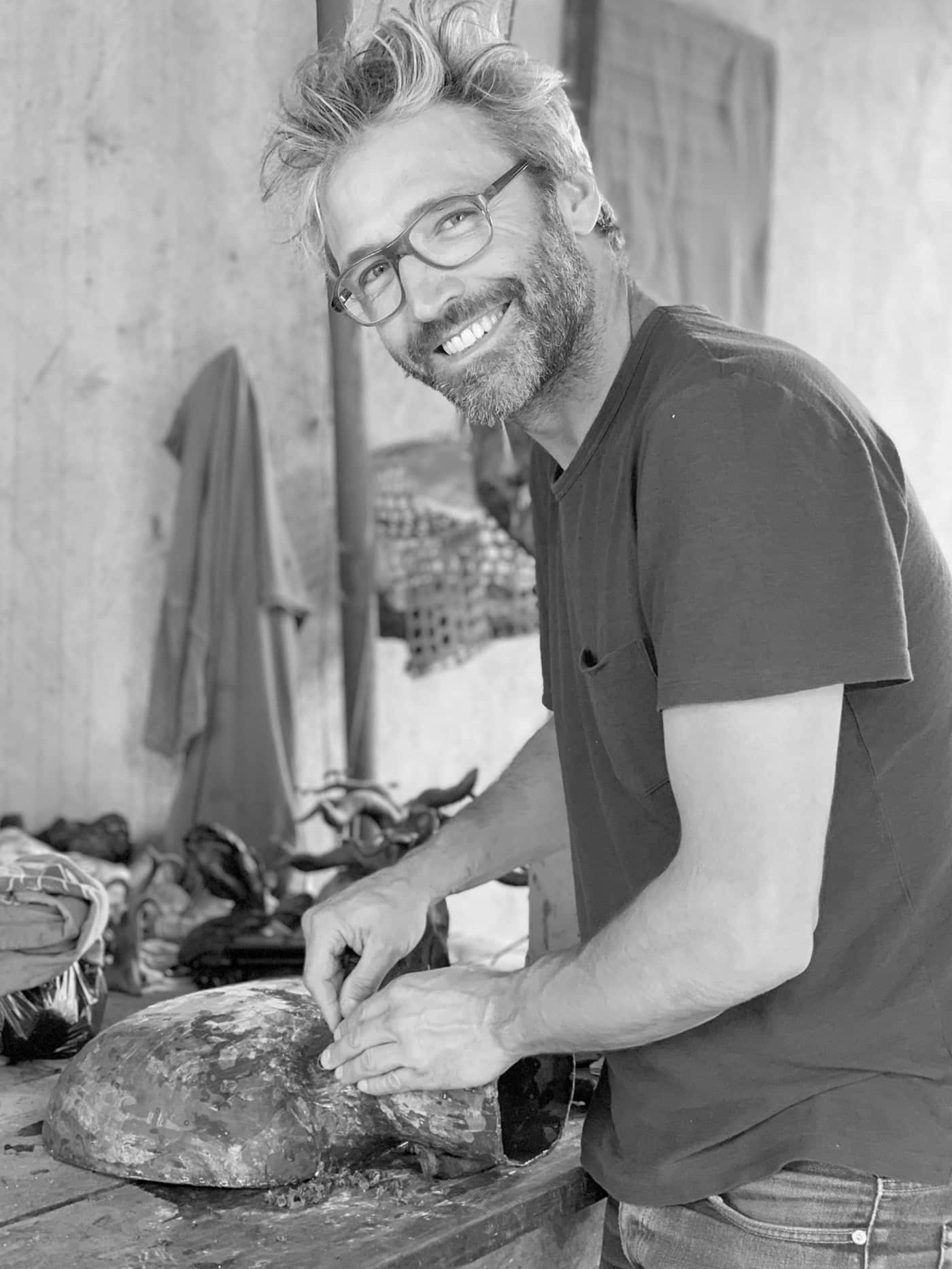

Designed by Noe Duchaufour-Lawrance

Maison Intègre is set to launch a new collection in collaboration with the multifaceted French designer Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance, whose inventive approach to the quintessential shapes found in Tiebélé, a traditional Kassena village located in the south of Burkina Faso, as well as other elements ever-present in the Burkinabe culture, has allowed him to create seven sculptural pieces that counterpart each other.

After Ambre Jarno, the founder and Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance first met in Paris in 2018, they discovered that their respective projects, Maison Intègre and Made in Situ, had a lot in common. Ambre invited then Noé to think about a possible collaboration.

Fifteen years earlier, Noé had visited the Bandiagara cliffs in Mali, another region of West Africa that is very hard to reach nowadays for security reasons. There, he had discovered ladders made of one single piece of wood, a common object in West Africa, particularly in the Dogon and Lobi cultures. The iconic Y shape was the first inspiration that came to Noe’s mind, with the idea of designing a sculptural lamp. “The idea of using only one material really spoke to me. I was impressed by the purity of the Y shape. It’s a special shape mostly because of its fragility: there’s only one leg, but the two arms facing upward and leaning against a surface make it extremely stable”, Noé says.

She invited him to take an immersive trip inside Burkina Faso, knowing that Noé would be sensitive to the beauty of local crafts, their associated know-how and their strong materiality. She invited him to take a long-winded journey in Burkina Faso. She also showed him images of the quintessential shapes found in Tiebélé, a traditional Kassena village located in the south of Burkina Faso, another red zone impossible to visit nowadays but which Ambre had had the chance to discover a few years earlier. These images, as well as other elements ever-present in the Burkinabe culture, such as the PALABRE chair, constituted the inputs that Noé received.

ABOUT THE DESIGNER

Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance

Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance is a designer working across a vast array of crafts and materials to create different pieces depicting his own nature-driven narrative. His approach to design is grounded on his innate ability to combine simplicity and an honest desire to create pieces that last. From architecture to furniture, from interiors to bespoke collections, Noé has a unique sense of respect for the past even when his eyes are on the future.

PIECES

Available on order

MAKING OF : ÉCHO LAMP

THE MAKING OF THE ÉCHO LAMP

The creation of a piece requires the participation of several bronze working trades. Up to fifteen artisans work together in the Maison Intègre workshop. Three master bronzers are at the controls and around them, several small teams work on the manufacturing stages: creation of the molds, extraction of the wax, casting of the molten bronze, cleaning, welding and finishing.

All our pieces are made by hand, using the ancestral technique of lost wax from recycled metals.

In late 2018, Wallpaper magazine invited us to collaborate with Brendan Ravenhill to create a piece for the Wallpaper Handmade exhibit, « Love. » Together we created a lamp that would embody the theme of love. The resulting design is a lamp in two parts that engage in a relationship with each other. One part is a light source that cradles a bulb in a brass shell, the other is a stand alone reflector that captures and bounces the light back in a soft reflected glow.

STEP 1

THE BEESWAX MODEL

A model of the piece is made out of beeswax. In Burkina Faso, it can be very difficult to handle the wax due to the heat. The country is close to the Sahel region and the temperature can reach 48°C.

In the case of a series of the same object, a plaster mold is built up on the wax model to easily replicate the model. In the case of unique pieces, plaster is not needed. Drains and air-vents are added to enable the melted wax to flow. These same channels will be used to cast the molten metal.

STEP 2

THE CLAY MOLD

The wax model is wrapped up in many layers of a mix of clay and horse dung. The whole is secured with metal wires and then baked for a few hours depending of the piece’s proportions.

STEP 3

REMOVING THE WAX

Once the clay has hardened and the wax melted, the melted wax is evacuated and put aside for reuse.

The wax area is now empty and ready for bronze to be poured in.

STEP 4

THE BRONZE CASTING

Bronze is made from recycled metals such as taps, screws and bolts. They are heated to about 1200°C in a melting pot dug into the ground. When the fusion occurs, the bronze is poured in the clay mold. The metal is left to cool and harden in the clay moulds for about an hour and a half.

STEP 5

EXTRACTION AND RAW FINISHING

When cooled, the mold is extracted and the clay is broken away from the bronze. The wires are removed and the surface is cleaned-up. If needed, some repairs are done. The lamp’s surface is then finished for the team in France to add the special finishes.

STEP 6

FINAL FINISHING

The final finishing stage and the patinas are provided by our affiliated workshop in the south of France.