RAPHAËL ET NOËLIE SAWADOGO

RAPHAËL AND NOËLIE SAWADOGO

Designers and weavers

“I learned to dye and I liked it, I love creating!”

Raphaël Sawadogo has already lived more than ten lives. In wood craftship, in certification, abroad, he worked in many different jobs, sometimes very well paid, until becoming an employee of a weaving workshop. “I was the boss’s right-hand man, a long-time friend, I helped him in particular with administrative management.” Then his friend tells him of an imminent departure to the United States and the closure of the workshop. “I was in danger!”. It was four years ago. He decides to learn dyeing, and it’s a revelation. “I really like it, and it provides a living for my family.”

At his side, Noëlie, his wife, creates and weaves the prototypes. The couple is settled in the courtyard of their house in Cissin, Ouagadougou. A 10-meter loom is there, carrying the threads of the creation in progress.

“We weave Faso dan Fani, from local cotton, organic one as often as possible.”

Faso dan Fani, which has returned to fashion thanks to the national preference given to local creations, has not generated any increase in activity among them. “But we have added value: we weave 40 thread, while the others weave 20.” A much finer and more elegant thread than the traditional dan Fani, which may be a little heavy to carry sometimes.

Raphaël and Noëlie also rely on sobriety to differentiate themselves: “no golden threads here, nor garish patterns”. In fact, their loincloths are either “dirty white”, that is to say ecru, or pastel colors. Because Raphaël favors the natural dyeing of his yarn, based on leaves, roots, bark or stones. And even when he has to use chemical dyes for financial reasons, he sticks to a range of colors close to those obtained by natural dyes. Once the yarn has been cleaned by boiling, the pattern created by Noëlie and the prototype woven, four women will weave the loincloths which will be sent to customers.

Raphaël works with individuals but also couturiers, and not the least. François 1er, a renowned Burkinabè designer, was seduced by the finesse of his Dan Fani and the delicacy of his patterns. “And we are among the only ones to weave 45 cm wide, where the others tend to weave 30 cm wide.” The Sawadogo couple’s demands for final quality and the difficulty of weaving such a fine thread mean that some women refuse to weave, because “you have to be calm, listen to advice and accept criticism” emphasizes Raphaël.

In March 2016, the revival of Dan Fani and the presidential decision to produce a national loincloth in this cotton caused a thread break. “There were none left, anywhere”, remembers Raphaël, who had to part with 6 of his weavers. Today, they have settled back into other activities and do not wish to return. Raphaël is therefore faced with the problem of every growing craftsman. Not enough hands to increase the quantity, and therefore not enough income to hire 6 new employees and invest in the equipment that goes with them. But the tenacity and professionalism of the couple suggests that this state will not last forever, thanks to their numerous recommendations.

Moreover, the objectives are clear: “I have acquired a small piece of land, I want to build a workshop there to bring together all the stages from dyeing to the exhibition and sale of finished products.” And thus make the courtyard of their little house playable for their three children and the dog Tex.

“Faso Dan Fani weaving requires seriousness and precision to obtain a quality product that will stand out.”

FASO DAN FANI

FASO DAN FANI

Woven loincloth of the homeland

If ever there was a symbol of Burkinabe patriotism, it’s Faso dan Fani. In a country where the cultivation of non-genetically modified cotton is one of the country’s main sources of income, and where the tradition of weaving goes back a long way, these heavy cotton loincloths quickly became indispensable both for clothing and for furnishing and decorative fabrics.

“In all the villages of Burkina Faso, we know how to grow cotton. In all the villages, women know how to spin cotton, men know how to weave this thread into loincloths and other men know how to sew these loincloths into clothes. We must not be a slave to what others produce.”Thomas Sankara

When Captain Thomas Sankara came to power in the mid-1980s, Faso Dan Fani became a national symbol and a promoter of local know-how. Determined to promote the emancipation of women through work and the development of national production, Thomas Sankara issued a decree requiring his civil servants to wear Faso Dan Fani. “Wearing Faso Dan Fani is an economic, cultural and political act of defiance against imperialism”, said Thomas Sankara, whose political inspiration was essentially based on communism and anti-colonialism.

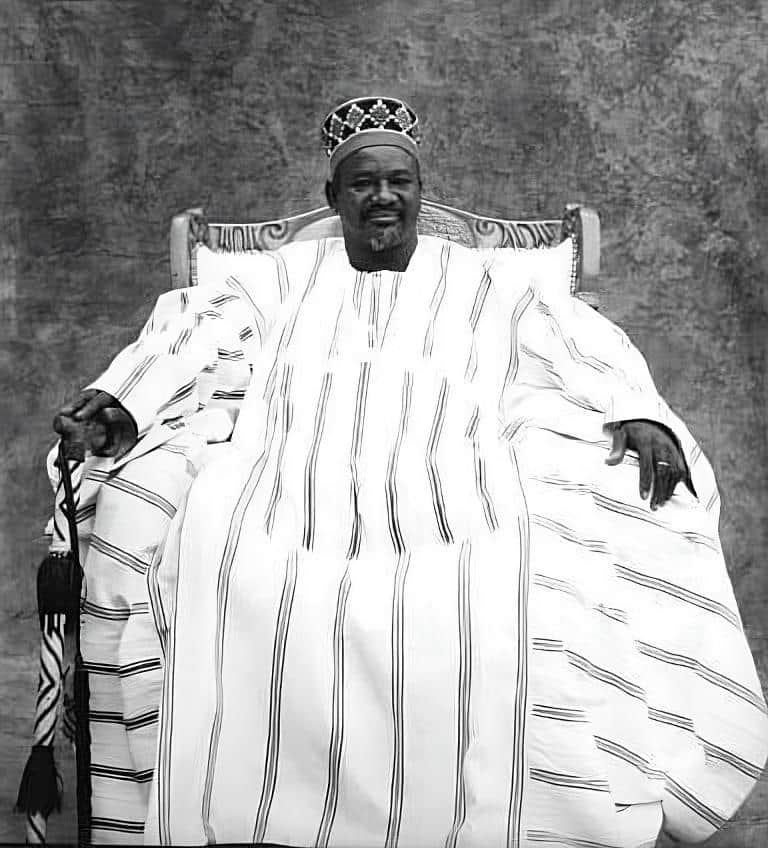

Although the daily use of this loincloth fell into disuse after Sankara’s death and the implementation of a much more liberal policy, the Faso Dan Fani has always remained the basis for the production of festive and ceremonial clothing, with the Naba – village chiefs – wearing it for every occasion. The first of these, the Mogho Naba, emperor of the Mossi, always wore a Faso Dan Fani when appearing in public or receiving audiences in his palace in Ouagadougou.

The revolution that took place in 2014, which ousted the dictator in place since the death of Sankara, raised an incredible wind of patriotism among Burkinabè. Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, President democratically elected at the end of 2015, brought the port of Faso Dan Fani up to date, himself wearing it at each of his appearances, including on official trips abroad. If the use of Dan Fani has not been made compulsory this time, it is however very favored. Each political demonstration sees the statesmen dressed in the traditional outfit woven in this heavy cotton, and the so-called “March 8” loincloth, published each year in honor of World Women’s Day for Equal Rights, and traditionally offered by all employers to their employees, is now from Faso Dan Fani.

Robust and natural, the Faso Dan Fani has become the symbol of a Nation proud of its roots and its know-how.

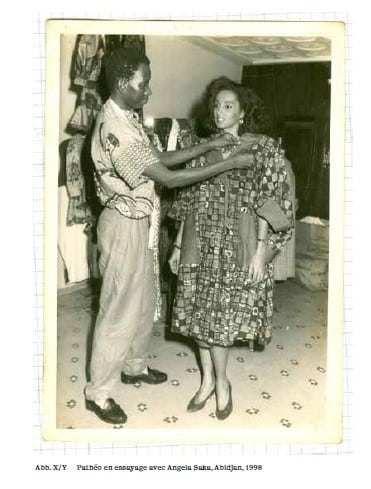

“Today Faso Dan Fani is highly valued around the world. It is the most expensive and best African fabric nowadays."Pathé Ouedraogo, known as Pathé'O, Ivorian designer

HORSEMEN FROM BURKINA FASO

HORSEMEN FROM BURKINA FASO

If you come to Burkina Faso, it’s not uncommon to come across a horse rider pacing the streets. The horse, emblem of the country, has a very close relationship with the burkinabè people.

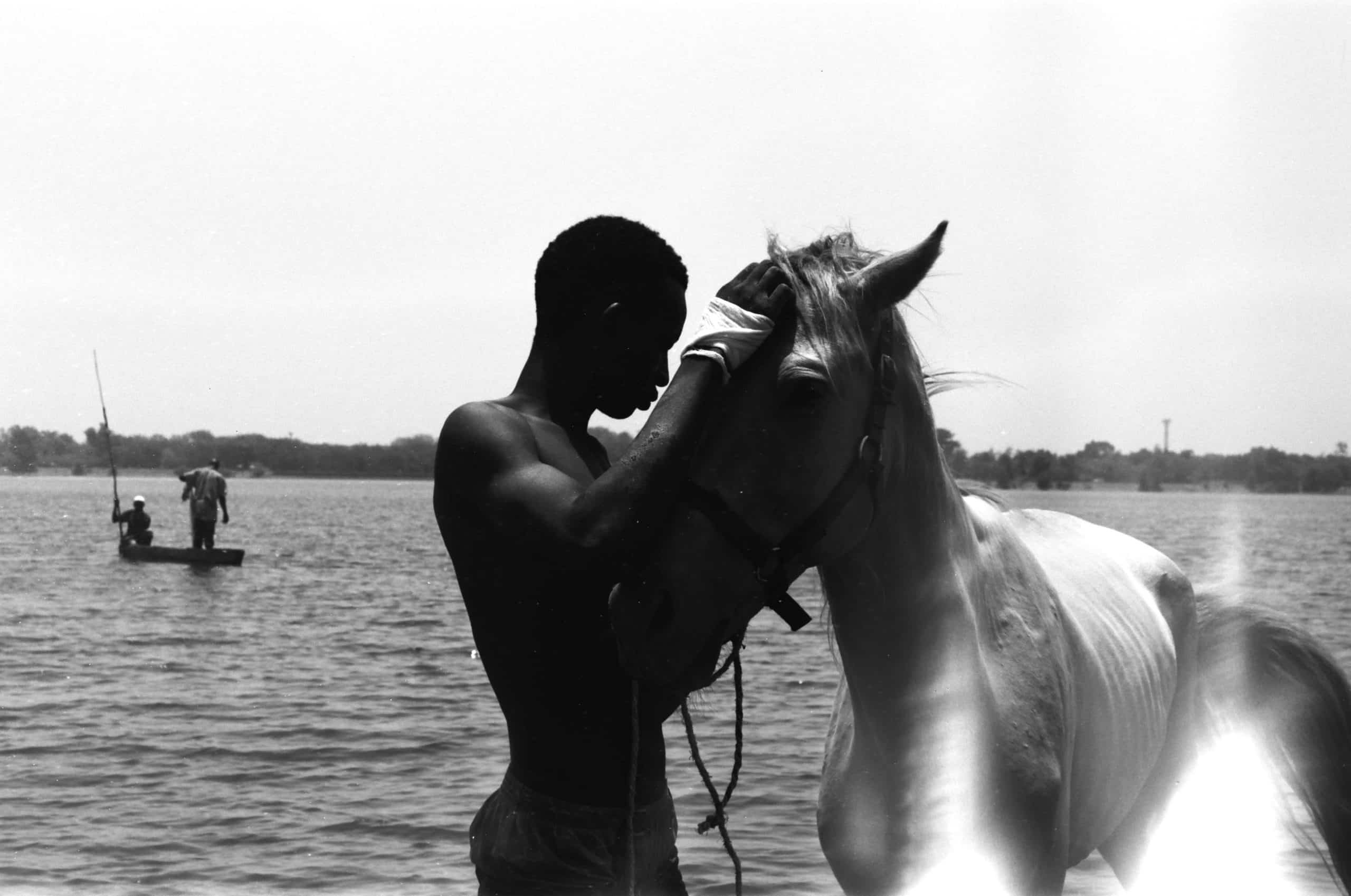

This connection originated in the legendary tale of Princess Yennenga and an exiled Malinke prince. Yennenga means “slender”, and is the founder of the Moogo kingdom uniting the Mossi peoples of present-day Burkina Faso. She was the daughter of King Nedega, an authoritarian and loyal king who ruled over the Dagomb peoples. The princess was passionate about horses, but despaired of being able to ride as men did.

Rebellious and reckless, she convinced her father to allow her to ride alongside him and became a fierce warrior. Following a dispute with her father, he threw her into prison, but the princess managed to escape and rode away on her favorite mount, a white stallion. During her escape, she met Prince Malinké, with whom she fell madly in love. The result was Prince Ouedraogo, meaning “stallion” or “male horse”.

Today, the “Ouedraogo” surname is one of the most common in Burkina Faso. The white horse on which the princess escaped has become the country’s national emblem.

This legend, passed down exclusively through Mossi oral tradition, has maintained a widespread passion for horses and their sacred role in the country. There was also a prestigious cavalry in medieval times, which disappeared with colonialism. Since then, this tradition has left a strong cultural legacy and a real passion for horses throughout the country.

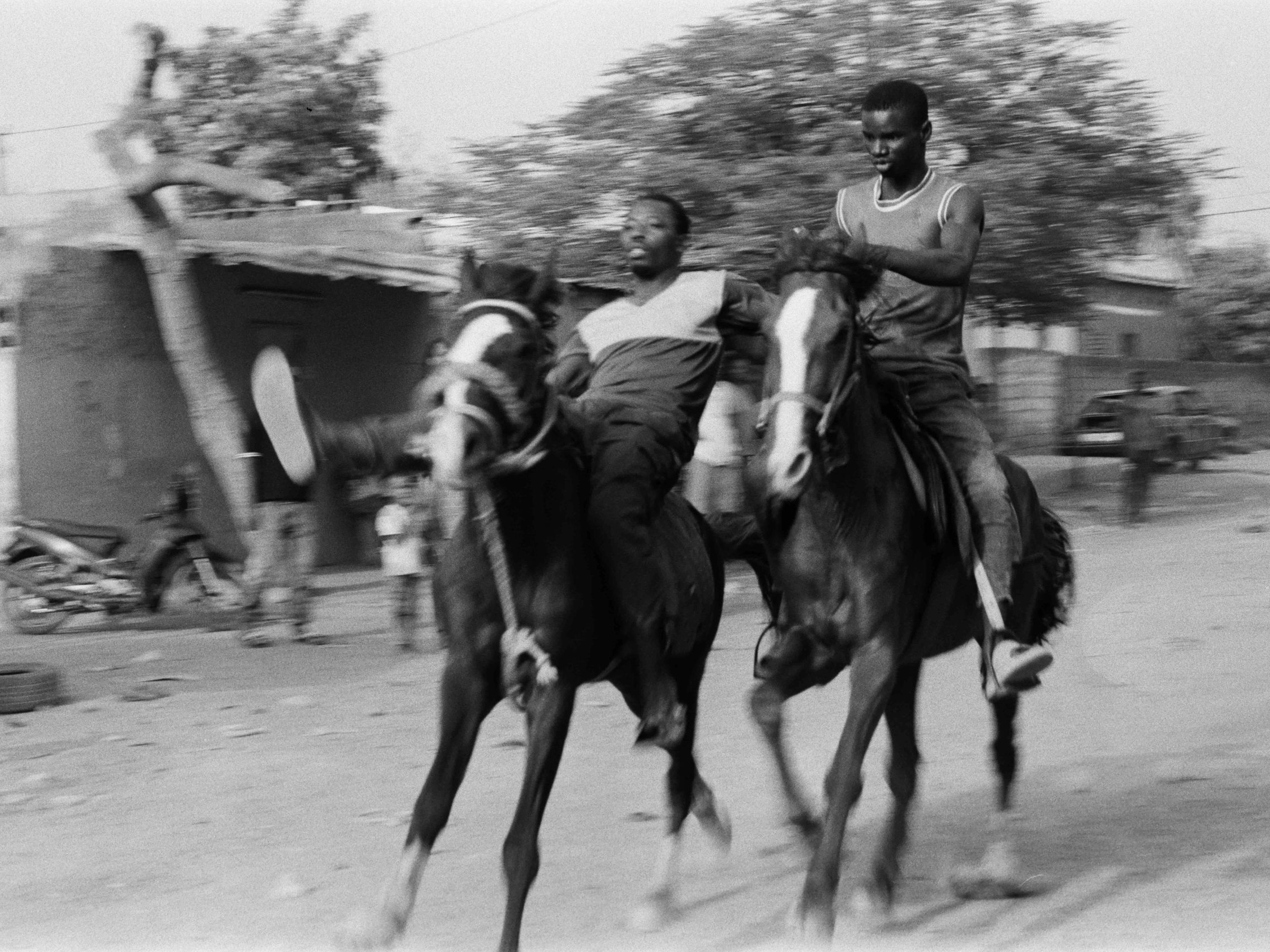

The equestrian tradition has resurfaced in a more marginal, urban form. It is developing alongside Burkina Faso’s ancient equestrian tradition, bringing it a new lease of life and a youth proud of its origins.

Only a few of the country’s wealthiest families own horses in the city, so young riders take to the streets and mingle with the capital’s frenetic traffic. Meeting in front of a bar or nightclub, they can be found at ceremonies or shows. The equestrian cult of nobility and beauty is remembered by all. It’s also common to come across horses roaming freely, sometimes stopping in front of houses simply to graze – they are the kings of the city.